There are two hundred of them. The photos depict signboards, announcements, traffic signs and posters. For instance:

CLUB “TIGER”/ DISCOTHEQUE / DATE 15.10, this yr. time…

“Date: 15.10”—as in a police report. Otherwise, without that “date”, Polish citizen might think 15.10 is the result of a basketball game. The abbreviated phrase “this year” clinging to the name of the month. The exact time cannot be read though, as it got wrapped around the pole.

I don’t know about you, but this kind of date format reminds me communist Poland immediately. The invasion of the stiff, bureaucratic language was a distinctive feature of that time. And a favorite motif of poems, satirical cartoons and students’ songs.

What year was that? Going through the slides we get some more tips.

AMERICAN MOVIE “TAXI DRIVER”, RATED FOR ADULT AUDIENCES ABOVE 18

The American premiere took place in 1976, but foreign films arrived in Poland with a delay. When the poster was displayed at the “Oka” cinema, Jodie Foster must not have been so insanely young anymore.

RATION STAMPS FOR SUGAR ARE DISTRIBUTED…

Any historians of the food rationing system in the house? Anybody remembers when the stamps for sugar were introduced? And here is the decor to celebrate the 35th anniversary of the Polish People’s Army. We just have to know the date, from which we count the history of our armed forces. No need to bother with Wikipedia. The next slide brings the answer: the local section of the Society for Promoting Physical Culture announces the subscription to its judo, bodybuilding and swimming sections. The 1978/79 season is about to begin.

Autumn 1979. The beginning of academic year. Warm weather. Kids are playing football. Young people in blue jeans are running along Piotrkowska street (the place is no mystery). The winter is yet to come. Nobody knows it will be called the Winter of the Century. Soon trains carrying coal will freeze on to the rails, the snow will cover the cities (snowdrifts can be seen on some of the photos). When the Spring comes, nothing remains the same. History will accelerate.

•

The novel “We” by Yevgeny Zamyatin was written in 1920. The plot is set in some distant future. The protagonist lives in a glass house (surely). His day starts with a workout. He makes synchronized movements together with a million of other citizens, all living in identical glass cells. Then he marches to work. He admires “the divine parallelepipeds of the transparent houses” (translation by Mirra Ginsburg) and delighted by the surrounding harmony and order, he gets into reflection:

“I suddenly recalled a picture in the museum: one of the avenues they had back then, after twenty centuries—a stunningly garish, mixed-up crush of people, wheels, animals, posters, trees, colors, birds … And they say it really was like that. It could have been like that. It all struck me as so unlikely, so idiotic, that I couldn’t help it, I burst out laughing.” (translated by Clarence Brown, Penguin Books, 1993)

•

However, in 1978 the houses remained nontransparent. The state didn’t dress citizens in identical uniforms. It didn’t change their names into numbers. It didn’t wake them up with bells or marching music.

Judging from the photos, all the state did was just nagging. Namely, it was about work safety. It nailed warning signs to the walls (messages weakened by stains, rust, and falling paint). For the rest of time, it kept repeating its spells.

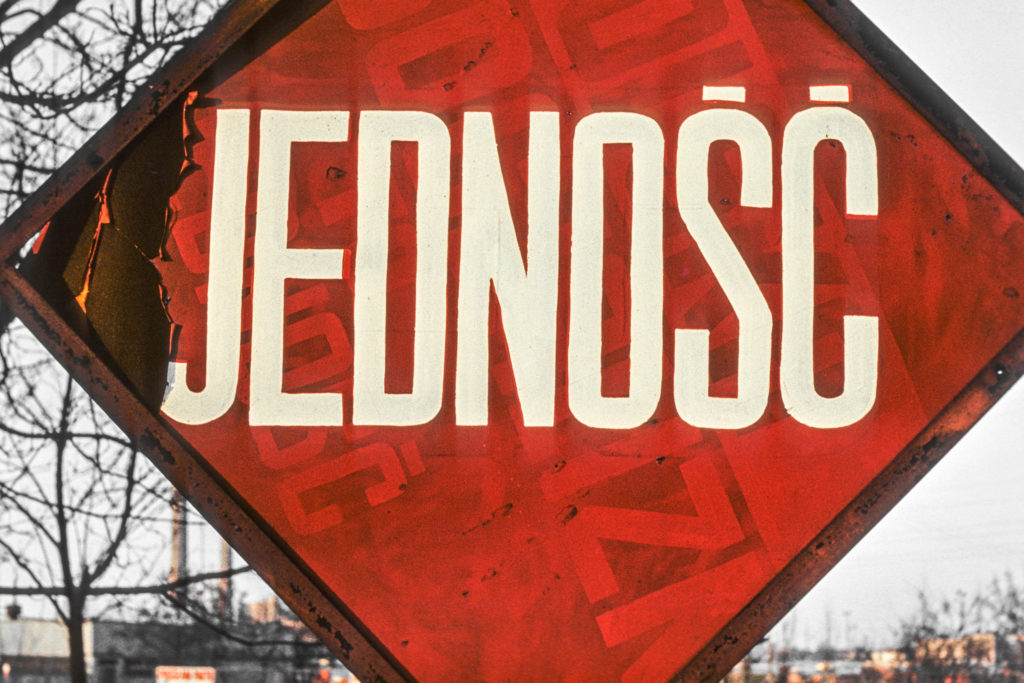

UNITY (white letters on red background)

NATION WITH THE PARTY (with bad kerning as well)

BUILDING POLAND OF OUR D… (the rest of “dream” collapsed together with the fence)

In the set of 200 slides, propaganda decorations make less than 10%. All incredibly boring.

It doesn’t mean that the system gave up its Orwellian ambitions. A year earlier, in 1977, the Cracow censor fled to Sweden, carrying a thick file of instructions for the press and publication inspectors. For instance:

– “Do not publish any information on the sale of meat to the USSR by Poland.”

– “Do not allow any criticism of decisions concerning wages or current social policy.”

– “Do not publish any information about coffee consumption.”

In Zamiatin’s naive dystopia, social life was organized as a train timetable. In real socialism, even trains did not stick to the schedule. But, it was forbidden to write about it.

The revolution was not about making order. Perhaps that’s why, without any regrets, it left behind avant-garde art, constructivists, visionaries dreaming of glass houses and modern typography.

Totalitarianism, even a partial one, proved to be messy, chaotic, and irrational. It developed from one purge to another. From one campaign to another. From an abandoned plan to an uncompleted investment.

The landscape of Łódź also remained chaotic, although the phrase “a stunningly garish” doesn’t fit the dark streets, old walls and smog visible in the pictures.

•

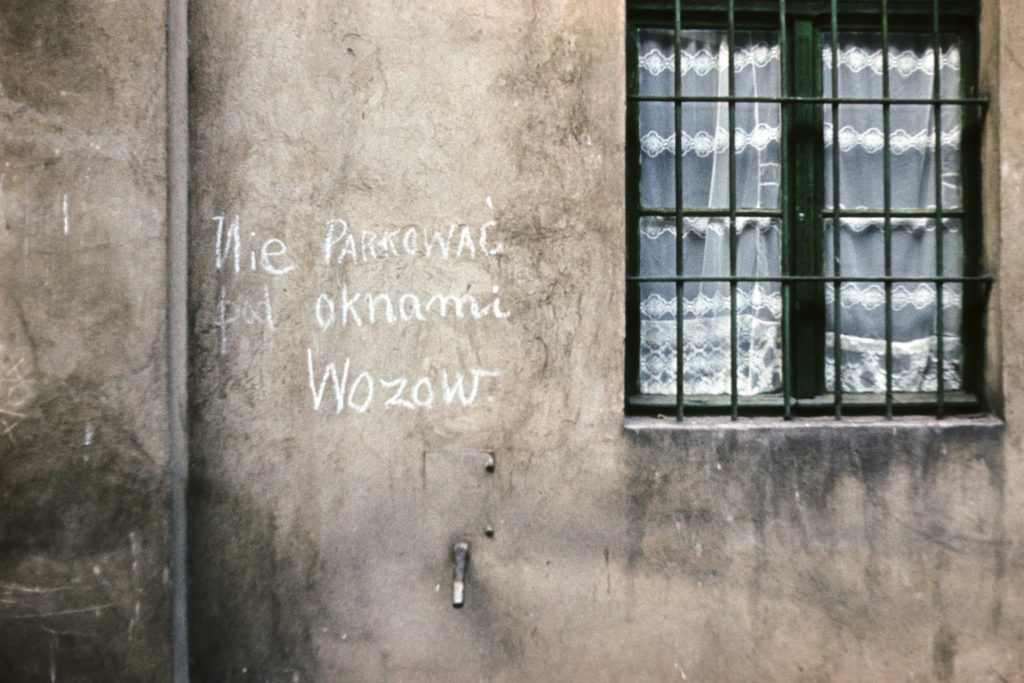

DO NOT PARK CARS / NEAR THE WINDOWS

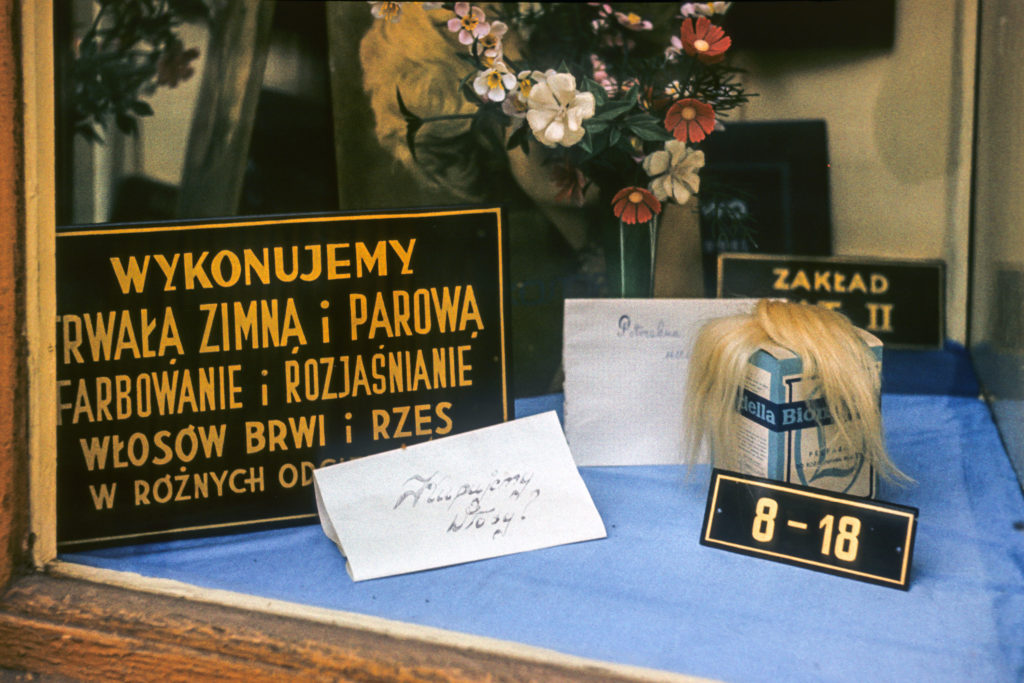

STEAM PERM

EMBROIDERY MILITARY INSIGNIA

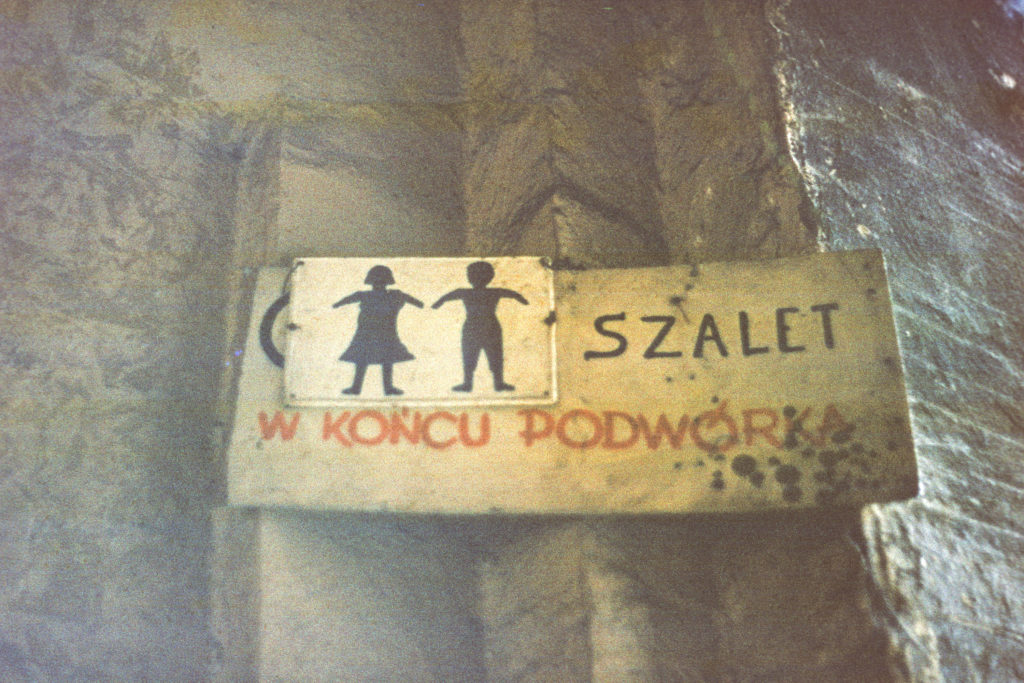

TOILET AT THE END OF BACKYARD

Empty storefront covered with yellow fabric. A small note: FOR SALE (somebody colored the counters of letters). We do not need much more to imagine a sad movie about an old craftsman.

Every single slide looks like a poster or book cover. That’s the power of framing. The detail cropped by the frame gains meaning. An irrelevant component becomes the main character. The key element of an unknown story. We see here both the exoticism and familiarity. We may think that the shot was taken by one of us, but at the same time by a complete stranger. Someone who gazed at perfectly familiar things but changed visual focus. Squinted his eyes—like an ambitious student of a drawing class —and looked at the walls of his city as if he saw them for the very first time.

•

There are no indiscrete shadows of the photographers in the frames, nor unintended self-portraits in window panes. All we know is that the photos were taken by the students from Krzysztof Lenk’s and Jan Kubasiewicz’s studio.

This is how Lenk described his work in an interview made by Steven Heller.

“I am a designer driven by visual logic and visual reasoning, and my inspirations come from the Polish ‘constructivism’ and Katarzyna Kobro (…) rather than from the Polish poster (…). The graphic design curriculum I proposed at the Academy of Fine Arts in Łódź in the 1970’s, was an effort to consider newspapers, magazines, textbooks, timetables, and other printed media as equal components of the contemporary visual civilization, in which the society functions.”

The mention of timetables reminds me of old constructivist utopias.

*

It was an example of Jan Kubasiewicz’s pedagogical intuition. To send students to the city. Force them to leave their safe island, the modern building of the school—of which Lenk once mentioned sarcastically “the architect’s irresistible urge to build on a former garbage dump something in an intensely Californian style.”

And here is the student patrol treading the foreign territory. The constructivists document visual chaos. Lack of logic. They record all possible offenses against legibility and functionality. As well as minor misdemeanors of the evidence of pride, ignorance, aesthetic indifference, silly snobbery (look at those Western-style fonts used to brand the JEANS BOUTIQUE on its signboard).

Sometimes the scouts find examples of humor and graphic imagination. Traces of an old tradition of lettering or sudden glimpses of creativity.

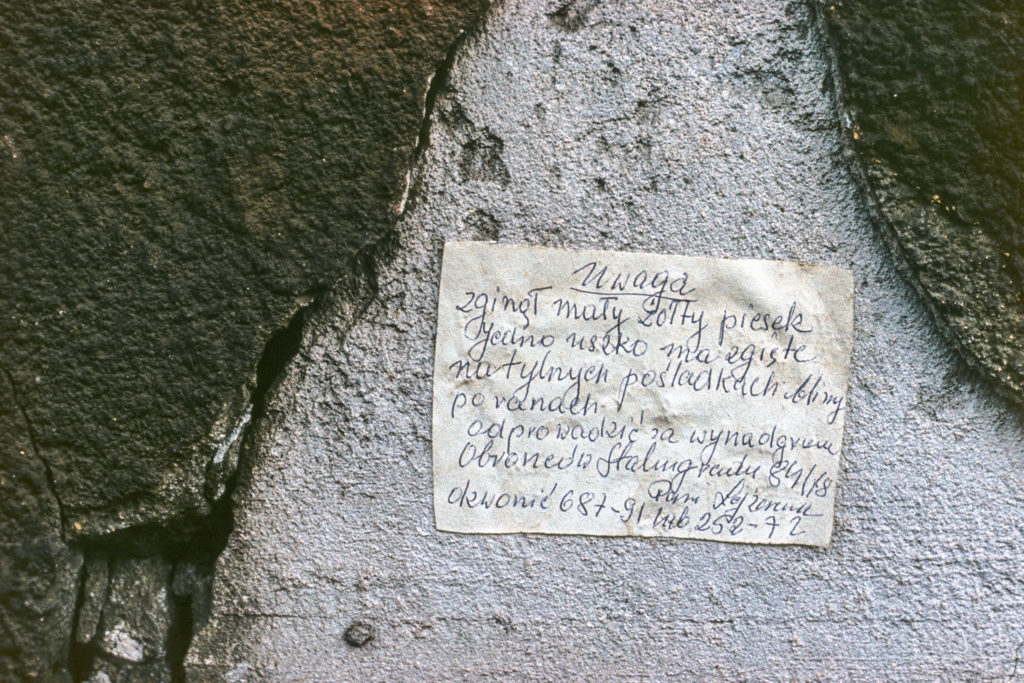

They also notice something more important. They see that in those clumsy forms it is life that leaves its traces. Sometimes grotesque, unhappy, pathetic—but still it’s life. The letters scribbled with the Zenit ball pen, painted with a stencil, cut out of styrofoam or glued from foil, are samples of life’s shapes.

ATTENTION/ SMALL YELLOW DOG MISSING/ ONE EAR BENT / SCARS ON BUTTOCKS

Maybe that Fall the students asked themselves the question whether a designer can help the world. Does the city need graphic designers? Can visual logic be imposed over the illogical space?

Łódź looks different forty years later, Jan Kubasiewicz has been teaching in the US for a long time, but the idea remained valid. This is how design education should begin—with a tour experience, with looking around and asking the question: Oh God, what shall we do with all of that?

Łódź looks different forty years later, Jan Kubasiewicz has been teaching in the US for a long time, but the idea remained valid. This is how design education should begin—with a tour experience, with looking around and asking the question: Oh God, what shall we do with all of that?

by Marcin Wicha

Download PDF of double-page spreads excerpted from the book Łódź ORWO. A Project by Jan Kubasiewicz, published by Bookidea, in Warsaw, Poland.